How Python processes your code

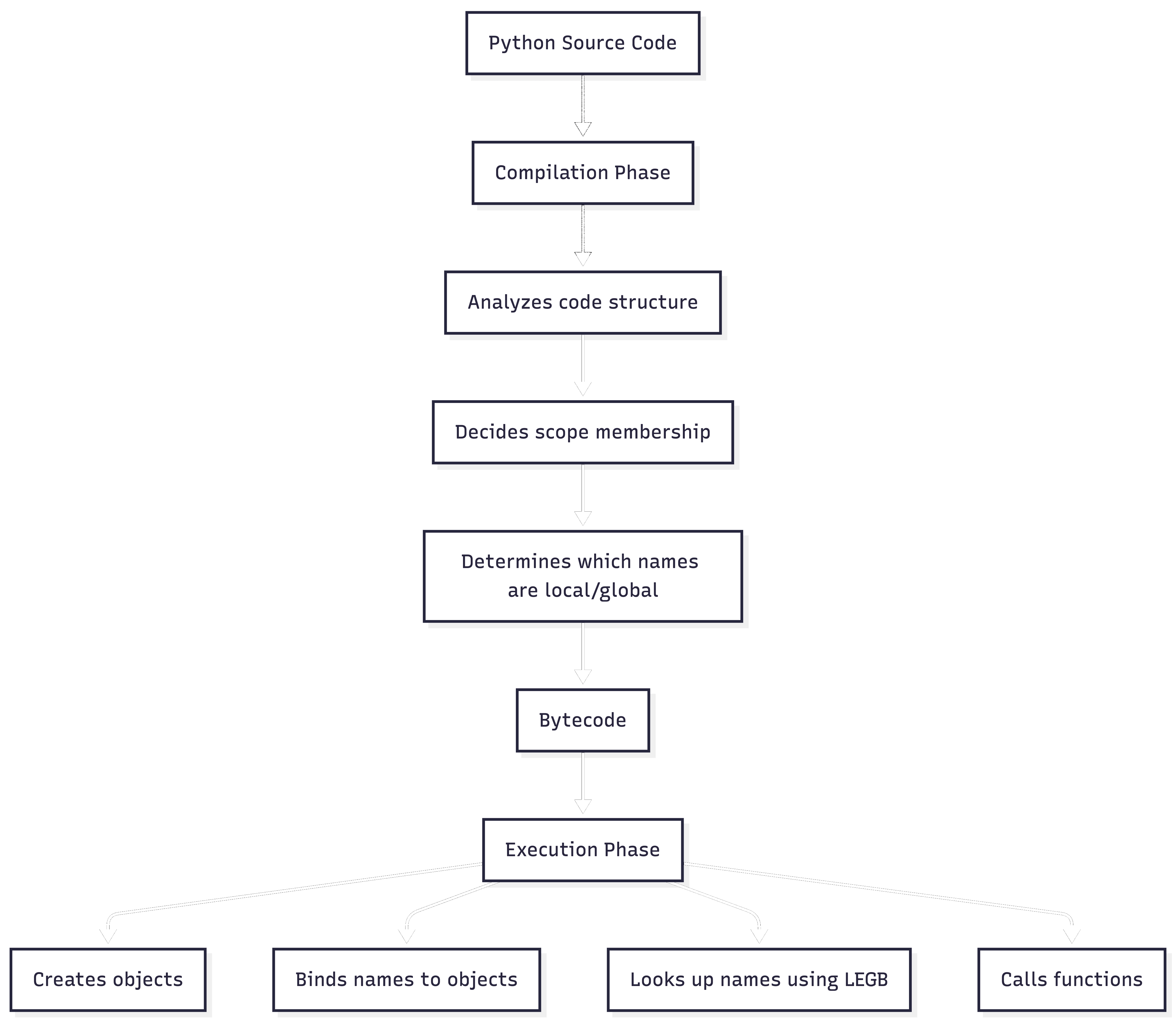

Python processes your code in two phases: compilation and execution. Understanding this split explains everything.

Compilation: What Python sees

Python executes code in two stages: compilation and execution. When Python compiles a code block (such as a module or function body), it analyzes the structure of the code. This includes where names are assigned, which names are referenced, and how scopes are nested.

def func():

print(x) # Is x local or global?

x = 5 # Assignment makes x local

Python sees the assignment x = 5 and decides: "x is a local name in this function." This decision happens before the function runs.

Compilation determines:

- Which names are local

- Which names are free variables (used but not assigned)

- Which names are global

- The structure of scopes

Execution: What Python does

When Python runs your code, it executes the bytecode. During execution, Python:

- Creates objects

- Binds names to objects

- Looks up names using LEGB (see below)

- Calls functions

- Raises exceptions

LEGB is the lookup order Python uses to find names:

- Local — names in the current function

- Enclosing — names in enclosing functions (closures)

- Global — names at module level

- Built-in — names like

len,print,int

Python searches these scopes in order, stopping at the first match. If it searches all four and finds nothing, you get a NameError.

Execution happens after compilation. The decisions made during compilation control how execution behaves.

NameError vs UnboundLocalError

These two errors come from different phases:

NameError: Python looked everywhere (LEGB) and couldn't find the name.

def func():

print(undefined_name) # NameError: name 'undefined_name' is not defined

UnboundLocalError: Python decided the name is local (during compilation), but you're trying to use it before it's assigned (during execution).

def func():

print(x) # UnboundLocalError: local variable 'x' referenced before assignment

x = 5

Why? Because Python saw x = 5 during compilation and marked x as local. When execution reaches print(x), Python looks in the local scope first, finds x exists (it's a local name), but it hasn't been assigned yet. Error.

This is why this works:

x = 10

def func():

print(x) # Works fine - x is free variable, looked up in enclosing scope

No assignment to x in func(), so Python doesn't mark it as local. It's a free variable, looked up at runtime.

How Python decides: local or not?

Python uses a simple rule: if a name is assigned anywhere in a function, it's local to that function. The assignment doesn't have to execute, it just has to exist in the code.

def func():

if False: # Never executes

x = 5

print(x) # UnboundLocalError anyway

Even though x = 5 never runs, Python saw it during compilation and marked x as local.

This is why global exists:

x = 10

def func():

global x

print(x) # Works - global tells Python: x is not local

x = 5 # Modifies global x

func()

print(x) # 5 (global x was modified)

# Output:

# 10

# 5

global tells Python during compilation: "don't mark x as local, it's global."

The global keyword

global changes how Python compiles your function. Without it, an assignment makes a name local. With it, Python skips the local scope and goes straight to global.

x = 1

def func():

global x

x = 2 # Modifies global x, not creating a local

func()

print(x) # 2

During compilation, global x tells Python: "when you see x in this function, don't mark it as local—it's a global name." During execution, assignments to x modify the global scope.

Without global:

x = 1

def func():

x = 2 # Creates a local binding

return x

func() # 2

print(x) # 1 (global unchanged)

Python sees x = 2 during compilation and marks x as local. The assignment creates a local binding, leaving the global x untouched.

You can use global even if the name doesn't exist yet:

def func():

global x

x = 10 # Creates x in global scope

func()

print(x) # 10

global is a compile-time directive. It changes how Python analyzes your function, not how it executes.

Compilation vs execution: The mental model

- Compilation analyzes code structure and decides scope membership

- Execution creates objects, binds names, and looks up names

- Scope decisions are made at compile time

- Name lookups happen at runtime

globalchanges compile-time decisions about scope

This split explains:

- Why

UnboundLocalErrorexists (local name used before assignment) - Why

globalis needed (it changes compile-time scope decisions) - Why scope is lexical (determined by code structure, not call site)

Everything in the names, binding, and scope guide follows from this two-phase model.